According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 29% of non-elderly adults (adults below the age of 65) covered by Medicaid have a mental illness.[1] In addition, of all non-elderly adults with mental illness, Medicaid covers 23% of this population. While the burden of mental health disease appears to be significant among the low-income adult population insured by Medicaid, reimbursement rates serve as one of the primary barriers limiting access to care for patients in need. When a mental health professional (i.e., psychiatrist) provides a service to a patient, the psychiatrist bills that patient’s insurance for that service. Services correspond to Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes, and in a fee-for-service (FFS) model, insurance companies or government programs (i.e., Medicaid) provide payment for each individual CPT code billed during an encounter.

In New Jersey, Medicaid reimburses around 50% of the amount that Medicare does for the same service.[2] A 2022 Government Accountability Office report highlights the impact of lower reimbursement rates, illustrating the reality that many mental health providers refuse to accept Medicaid (or other insurance types) and instead opt for cash-only payment models.[3] For low-income patients insured via Medicaid, this may make obtaining mental health services impossible and lead to increased unmet mental health needs. When physicians refuse to accept this insurance, this not only lowers the number of providers available to see patients; it also overburdens those providers that do accept patients with Medicaid. This, in theory, could lead to longer wait times for appointments, shorter appointment times, and increased burnout among providers, all of which could contribute to an increased unmet need among patients.

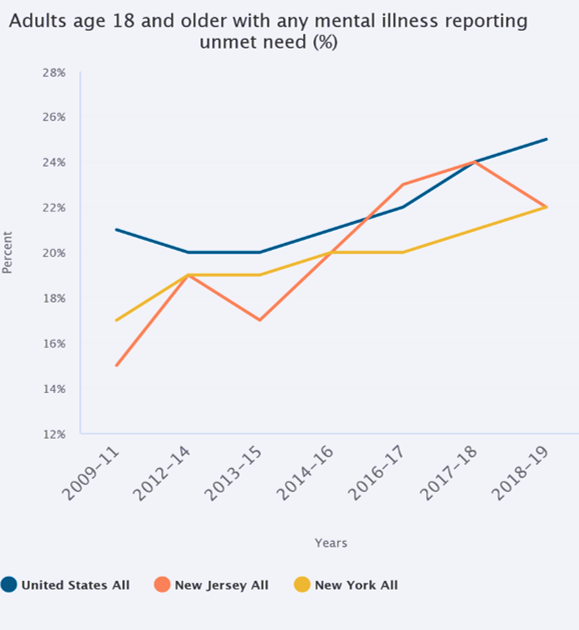

Between 2011 and 2016 in NJ, the percentage of adults 18 and older with any mental illness reporting unmet need increased from 15% to 20%, while the nationwide percentage remained at 21%.[4] From 2016 to 2018, this number increased to 24% in NJ, then fell to 22% in 2018-2019.[4] In New York, there has been a steady upwards trend since 2011, with the most recent data indicating 22% of adults with mental illness reporting unmet need in the past year.[4]

Comparison of unmet mental health needs between the U.S., New York, and New Jersey. [4]

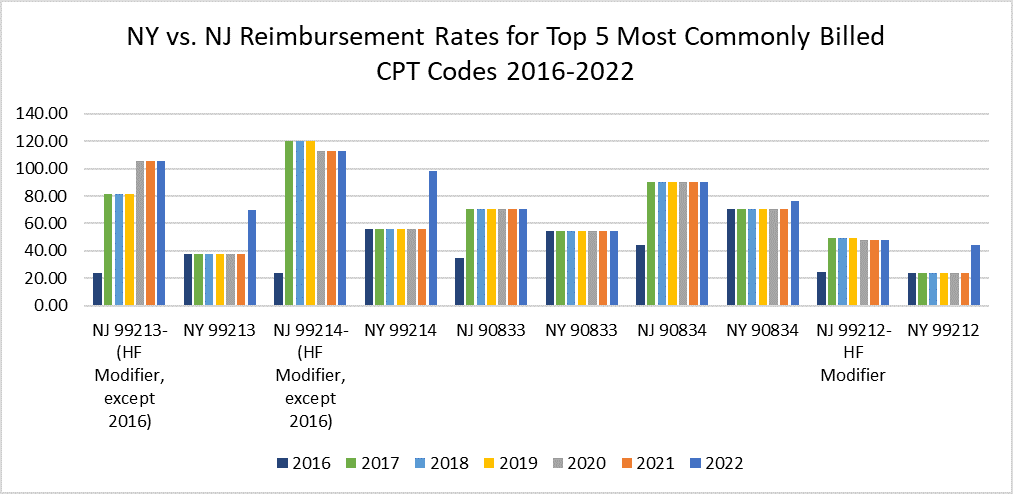

Unfortunately, this transition–which took place in 2016–has not led to financial sustainability for all mental health service providers. A 2018 survey conducted by the New Jersey Association of Mental Health and Addiction Agencies (NJAMHAA) found that the 27 organizations reimbursed via fee-for-service (FFS) that were polled operated with a deficiency of around $18 million from December 2017-December 2018.[7] There have been some increases in reimbursement rates since the FFS transition; for example, the maximum reimbursement rate for 60 minutes of psychotherapy with a patient almost doubled from $49.00 in 2017 to $90.26 in 2018.[8] However—excluding the increased funding seen during the COVID-19 pandemic—reimbursement rates for behavioral health (BH) services have not been increased in almost three years.[8]

Community-based programs appear to be bearing the brunt of this. Wage compression limits the attractiveness of these positions to mental health professionals, as discussed in this piece by Dr. Debra Wentz.[9] This has contributed to an ongoing struggle for certain BH programs to maintain their operations.[9] This struggle to continue operating may have led some BH service providers to close their doors, which, in turn, may have added to unmet mental health need seen throughout the state.

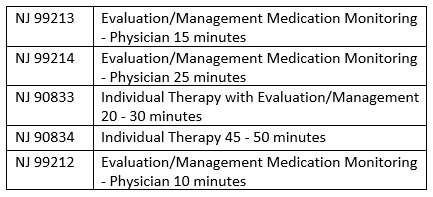

Despite this, New Jersey Medicaid reimburses relatively well for BH services. As shown in the table below, since the transition to FFS in mid-2016, NJ has paid providers more for behavioral health services than NY Medicaid for five of the CPT codes most commonly used by psychiatrists (see CPT Code Table for descriptions).[8] [10]

Why is it, then, that the unmet need for mental health services is comparable between these two states and was higher in NJ from 2016-2018?

Part of the reason may lie in the fact that there is such a small percentage of NJ psychiatrists who accept Medicaid. According to a 2021 MACPAC report, only 42.2% of NJ physicians accepted new Medicaid patients between 2014-2017, well below the 62.6% in New York and the national average of 74.0%.[11] Interestingly, this period coincides with a significant increase in the percentage of patients reporting unmet mental health need in NJ.[4], [11]

The data and opinions of mental health professionals highlighted in this piece illustrate several issues and raise multiple questions. There is a significant portion of adults with mental health illness in NJ who are unable to access adequate BH services. The reasons for this gap include comparatively low Medicaid reimbursement and low acceptance rates of patients with Medicaid among psychiatrists.

NY vs. NJ Reimbursement Rates for Top 5 Most Commonly Billed CPT Codes 2016-2022

Although the percentage of adults reporting unmet mental health need in NJ is below the national average, these are among the individuals who become high utilizers of the healthcare system (especially the ER) and have poor long-term outcomes. In addition, there are likely individuals who are not captured in the SAMHSA survey on which this data is based–primarily patients with transient housing in poor socioeconomic situations. It is possible that with increased acceptance of Medicaid by psychiatrists, more of these high-utilizers can receive BH services, decrease their frequency of emergency department (ED) visits, and achieve improved outcomes.

How does NJ go about increasing Medicaid acceptance? Part of the answer may be increasing Medicaid payment for BH services. Bill S2792, if passed into law, would increase Medicaid FFS payment rates to 100% of Medicare rates.[12] While this may help decrease the frequency of high-cost ER visits, additional efforts should be dedicated to identifying why certain BH programs are financially struggling in the current environment. By doing so, the state may be able to establish financial best practices for organizations offering behavioral health services in NJ to help ensure financial sustainability and a behavioral health services network that adequately serves all its patients. Financial transparency and collaborative efforts between the state and BH programs may be instrumental in ensuring that the percentage of unmet mental health needs in the state continues to fall.

–Behavioral Health and Mental Health are used interchangeably

–Provider includes both individual mental health providers and programs/organizations that offer mental health services.

–The reimbursement rates discussed apply to psychiatrists

CPT Code Table

Dr. Nduka Vernon (nv277@rutgers.edu) is a current Emergency Resident at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

References

[1] Saunders H, Rudowitz R. Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage of Nonelderly Adults With Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders in 2022. KFF. Published June 6, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/demographics-and-health-insurance-coverage-of-nonelderly-adults-with-mental-illness-and-substance-use-disorders-in-2020/#:~:text=Mental%20illness%20and%20substance%20use%20disorders%20are%20most%20prevalent%20among,and%2020%25%20of%20uninsured%20people.

[2] Medicaid-to-Medicare Fee Index Source: Epstein, M., Skopec, L., Zuckerman, S.,”Medicaid Physician Fees after the ACA Primary Care Fee Bump,” Urban Institute, March 2017. KFF: State Health Facts. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-to-medicare-fee-index/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedRows=%7B%22wrapups%22:%7B%22united-states%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[3] United States Government Accountability Office. Mental Health Care: Access Challenges for Covered Consumers and Relevant Federal Efforts.; 2022. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104597.pdf

[4] Adults age 18 and older with any mental illness reporting unmet need (%). The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/datacenter/adults-any-mental-illness-reporting-unmet-need

[5] TheNJDHS. Mental Health Fee For Service Rate Presentation. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=giXduNFw6lI

[6] Kaiser Family Foundation. Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier. KFF: State Health Facts. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[7] New Jersey Association of Mental Health and Addiction Agencies. Survey Results: Deficits in Fee-for-Service Programs. NJAMHAA. https://www.njamha.org/links/publicpolicy/Three_charts_FFS_Deficits.pdf

[8] Rate Information. NJMMIS. https://www.njmmis.com/hospitalinfo.aspx

[9] Debra L. Wentz. NJ deserves a stronger behavioral healthcare system as federal funds flow. northjersey.com. Published April 2, 2021. Accessed June 12, 2022. https://www.northjersey.com/story/opinion/2021/04/02/nj-deserves-stronger-behavioral-healthcare-system-federal-funds-flow/4836324001/

[10] NY Physician Manual. eMedNY. https://www.emedny.org/ProviderManuals/Physician/index.aspx

[11] MACPAC. Physician Acceptance of New Medicaid Patients: Findings from the National Electronic Health Records Survey. Published June 2021. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Physician-Acceptance-of-New-Medicaid-Patients-Findings-from-the-National-Electronic-Health-Records-Survey.pdf

[12] Senate Health, Human Services and Senior Citizens Committee Statement to Senate, No. 2792. Published June 23, 2022. https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/Bills/2022/S3000/2792_S1.PDF