Over the past several years, Governor Phil Murphy’s administration has instituted several nationally innovative environmental justice initiatives. In 2018, early in his first administration, Governor Murphy issued Executive Order No. 23 (E.O. 23), which acknowledged that “historically, New Jersey’s low-income communities and communities of color have been exposed to disproportionately high and unacceptably dangerous levels of air, water, and soil pollution, with the accompanying potential for increased public health impacts.” E.O. 23 additionally mandated that state agencies should consider “environmental justice in implementing their statutory and regulatory responsibilities.” Although an important step forward, this executive action did not directly establish new statutory authority – rather, it only set the stage for state agencies to make further decisions on how to address environmental justice concerns. In response, the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) began developing implementation guidance for E.O. 23 (which was eventually released in 2020).

There were three concrete outcomes of the NJDEP guidance: first, the establishment of a definition for environmental justice (EJ) communities[1]; second, the launch of an executive branch Environmental Justice Interagency Council; and third, the requirement of agency environmental justice action plans.

While the NJDEP was in the midst of developing this guidance for E.O. 23, the state legislature also passed a trailblazing Environmental Justice Law. The NJ EJ Law (A.B. 2212/S.B. 232) is a novel state law which authorizes the NJDEP to “deny or condition permits for certain pollution-generating facilities that would cause or contribute to adverse cumulative environmental and public health stressors that disproportionately impact overburdened communities” (according to subsequent NJDEP internal documentation). In other words, the EJ Law allows NJDEP to restrict future development of industrial facilities if it determines that such siting would be harmful to existing overburdened communities, therefore superseding the historical deference to municipal code in the siting of such facilities.

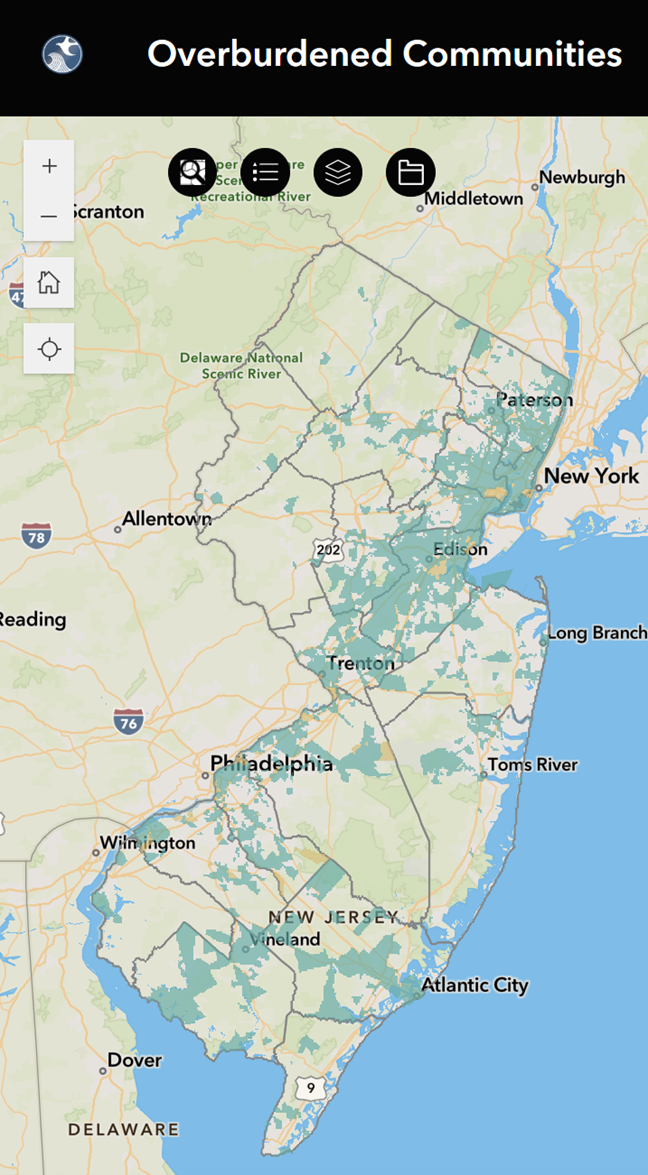

The EJ Law identifies overburdened communities (OBCs) as distinct from the E.O. 23 guidance defining EJ communities. To be considered an OBC under the EJ Law, a given census block group in NJ must meet one of three criteria:

1) 35% or more of households are low-income;

2) 40% or more of residents identify as racial/ethnic minorities; or

3) 40% or more of households report low English proficiency.

The EJ Law furthermore establishes eight types of covered facilities, including: incinerators, landfills, sewage treatment, scrap metal, medical waste, and several others. These facilities are now required (when seeking new/renewed permits and if located in an OBC) to publish EJ Impact Statements with information on the proposed site’s “adverse cumulative stressors,” host public hearings, and collect public written comments, all of which will then be assessed by NJDEP. In 2023, NJDEP officially adopted these new regulatory procedures and began implementing the EJ Law.

Image caption: Map of NJ OBCs, as produced via NJDEP’s Environmental Justice, Mapping, Assessment, and Protection Tool.

Key to the design process of the EJ Law was a sustained relationship – including frequent meetings – between NJDEP and a coalition of community-based organizations advocating for policies targeting cumulative impacts. It was this coalition, which included such organizations as the NJ Environmental Justice Alliance (NJEJA), that first proposed a focus on cumulative impacts in the early 2000s. (See for example a 2009 report from a cumulative impacts subcommittee of NJDEP’s EJ Advisory Council, populated by many of the same local advocates and researchers who would go on to participate in the development of the EJ Law ten years later.)

Still, time – plus resources dedicated to monitoring and evaluation – will tell if implementation of the EJ Law has led to a meaningful reduction in additional harm to OBCs. Furthermore, the scope of the EJ Law, though groundbreaking, is nevertheless still quite limited. It does not, for example, address such issues as pollution from existing facilities, types of polluting facilities outside of its eight identified categories, other forms of protective climate/energy justice policies for OBCs (such as mandatory emissions reductions or flood resilience strategies), or the “environmental and financial benefits” rather than just protection from harms.[2]

NJDEP also developed a website that tracks permit notices related to the EJ Law documents, which currently notes that 89 permits have had their review processes initiated (by 54 municipalities in 18 counties), but only one final decision has been made to date. In this decision, NJDEP conditionally approved a proposal from a regional public utility to build a new gas-powered sewage treatment facility, pending considerable operational limitations imposed by the department, such as only allowing the new facility to operate as a backup during emergencies like hurricanes.

References:

- Murphy, P. D. (2018). Executive Order No. 23. State of New Jersey.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. (2020). Furthering the Promise: A Guidance Document for Advancing Environmental Justice Across State Government.

- New Jersey Legislature. (2020). A.B. 2212/S.B. 232: Environmental Justice Law. Public Law 2020, Chapter 92.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. (2021). Administrative Order No. 2021-25.

- New Jersey Office of the Governor. (2023). Governor Murphy Announces Nation’s First Environmental Justice Rules to Reduce Pollution in Vulnerable Communities.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. (2023). Overburdened Communities. Environmental Justice, Mapping, Assessment, and Protection Tool.

- New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance. (2023). Cumulative Impacts Primer.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. (2009). Strategies for Addressing Cumulative Impacts in Environmental Justice Communities. Cumulative Impacts Subcommittee of the Environmental Justice Advisory Council.

- New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance. (2025). Statewide Policy Platform: 2025-2026.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. (2025). Environmental Justice: Administrative Order Meeting Notices by County.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. (2025). Environmental Justice Administrative Order Decisions.

- Fragoso, A. D. (2025). New Jersey agency sued for allowing fourth fossil-fuel plant in Newark. Earthjustice.

Footnotes:

[1] “Environmental justice communities are identified by three criteria: presence in a community of concern; the presence of disproportionate environmental and public health stressors; and the absence or lack of environmental and public health benefits” (DEP, 2020; p. 10).

[2] See NJEJA’s recent policy platform for an overview of these shortcomings and recommended future policy actions.