As a result of longstanding structural inequities, African American women endure greater trauma, socioeconomic disparities, and stress, and have less access to healthcare and social support during the perinatal period, which occurs from the beginning of pregnancy to a year after giving birth. With these factors, which can lead to poorer mental and physical health conditions, it is concerning that Black women remain one of the most understudied, underserved, and undiagnosed groups. This lack of research impacts the care provided and is reflected in the significant racial disparities in maternal health.

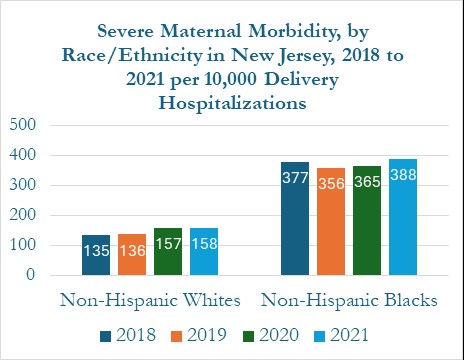

Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) is defined as unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery, and results in significant short- and long-term consequences for birthing people. In the United States, Non-Hispanic Black birthing people continue to have the highest SMM rate with 139 deaths per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations in 2020. Moreover, this rate has increased from 2019 (126.0). Both are disproportionately large rates compared to Non-Hispanic Whites (69.9 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations in 2020). These rates are also reflective in New Jersey (Figure 1). In 2021, Non-Hispanic Black birthing people continued having the highest rate of SMM with 388 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations; a rate which is more than double that of Non-Hispanic Whites in New Jersey (158.0).

Figure 1: A bar graph showing Severe Maternal Morbidity for Non-Hispanic Whites and Non-Hispanic Blacks in New Jersey from 2018-2021 Data Source: New Jersey Maternal Data Center, New Jersey Department of Health, 2021

Person-Centered Care

One strategy in addressing the racial disparities present in maternal care is providing person-centered care. The concept of ‘person-centered care’ has evolved and parallels patient-centered care, incorporating elements like empathy, communication, holistic care, and patient engagement. A study was conducted to understand the factors that contribute to positive and negative experiences of pregnant Black women in California using the validated Person-Centered Maternity Care (PCMC-US) scale. Higher scores were reported by Black mothers who saw the same provider from prenatal to postnatal and had at least one provider at birth that shared the mother’s race. These significant (p <0.001) results indicate the importance of continuity of care and racial concordance in improving person-centered care. There is also an explicit desire from Black women for same race healthcare providers. According to previous research, patients with less exposure to the healthcare system and a greater mistrust of the medical system have benefited the most from this racial concordance.

However, cultural competence and person-centered care are two distinct ideas. Healthcare providers should seek to also incorporate cultural competence into person-centered care to provide healthcare that is both equitable and of high quality. Person-centered care calls for a more holistic approach that integrates an individual’s whole “context,” which includes family members, caregivers, and individual preferences and beliefs to whole person well-being.

Future Directions

In delivering person-centered care for birthing mothers, the introduction of the CMS Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH) model is specifically aimed at creating a comprehensive, whole-person approach to perinatal care. It aims to address the physical, mental health, and social needs experienced during and after pregnancy. Furthermore, this care and payment model leads to enhanced maternal health care for individuals enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The application deadline for TMaH was September 20, 2024. If New Jersey is one of the fifteen State Medicaid Agencies selected for this funding opportunity, it will be eligible for 17 million dollars from January 20, 2025 to January 19, 2035. New Jersey should consider participating in this 10-year program as it could improve maternal health and birth outcomes by helping service providers in the state implement a holistic person-centered approach for expectant and new mothers.

Bernice Amankwah is pursuing her bachelor’s degree in health administration at the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University. She was also one of eight students selected to participate in the New Jersey State Policy Lab’s third annual Summer Internship program.

Works Cited

- Altman, M. R., Afulani, P. A., Melbourne, D., & Kuppermann, M. (2023). Factors associated with person-centered care during pregnancy and birth for Black women and birthing people in California. Birth, 50(2), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12675

- Barlow, J. N. (2016). WhenIFellInLoveWithMyself: Disrupting the Gaze and Loving Our Black Womanist Self As an Act of Political Warfare. Meridians (Middletown, Conn.), 15(1), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.2979/meridians.15.1.11

- Baye, E., Armstrong, D., Mayo, E., Iii, S. L. F., & Mustafa, M. (2021). HEALTH CARE QUALITY AND INFORMATICS.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, May 20). Severe Maternal Morbidity. Maternal Infant Health. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/php/severe-maternal-morbidity/index.html#:~:text=Severe%20maternal%20morbidity%20%28SMM%29%20includes%20unexpected%20outcomes%20of.

- Ekman, I., Swedberg, K., Taft, C., Lindseth, A., Norberg, A., Brink, E., Carlsson, J., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., Johansson, I. L., Kjellgren, K., Lidén, E., Öhlén, J., Olsson, L. E., Rosén, H., Rydmark, M., & Sunnerhagen, K. S. (2011). Person-centered care–ready for prime time. European journal of cardiovascular nursing, 10(4), 248–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

- Håkansson Eklund, J., Holmström, I. K., Kumlin, T., Kaminsky, E., Skoglund, K., Höglander, J., Sundler, A. J., Condén, E., & Summer Meranius, M. (2019). “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029

- Hirai, A. (2023). Severe Maternal Morbidity: Trends and Disparities Advisory Committee on Infant and Maternal Mortality. Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA). https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/infant-mortality/meetings/hirai-severe-maternal-morbidity.pdf

- Lasser, K. E., Mintzer, I. L., Lambert, A., Cabral, H., & Bor, D. H. (2005). Missed Appointment Rates in Primary Care: The Importance of Site of Care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16(3), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2005.0054

- Nelson, T., Cardemil, E. V., Overstreet, N. M., Hunter, C. D., & Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2024). Association Between Superwoman Schema, Depression, and Resilience: The Mediating Role of Social Isolation and Gendered Racial Centrality. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 30(1), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000533

- Nelson, T., Ernst, S. C., Tirado, C., Fisse, J. L., & Moreno, O. (2022). Psychological Distress and Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Services Among Black Women: the Role of Past Mental Health Treatment. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(2), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-00983-z

- Ofrane, R. H. (2024). BIRTH CENTERS IN NEW JERSEY: A QUALITATIVE AND POLICY ANALYSIS OF BARRIERS TO EQUITABLE BIRTH CENTER ACCESS.

- Perinatal Mental Health Service: Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. (2024). https://www.sabp.nhs.uk/our-services/mental-health/perinatal

- Saha, S., Beach, M. C., & Cooper, L. A. (2008). Patient Centeredness, Cultural Competence and Healthcare Quality. Journal of the National Medical Association, 100(11), 1275–1285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31505-4

- Santana, M. J., Manalili, K., Jolley, R. J., Zelinsky, S., Quan, H., & Lu, M. (2018). How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expectations, 21(2), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12640

- Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH) Model | CMS. (2023). Www.cms.gov. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/transforming-maternal-health-tmah-model