As discussed in our previous blog entry on our development of a State AI Readiness Index, artificial intelligence is transforming industries, economies, and governments around the globe. However, despite its increasing influence, the readiness for AI adoption in governance differs significantly across individual U.S. states.

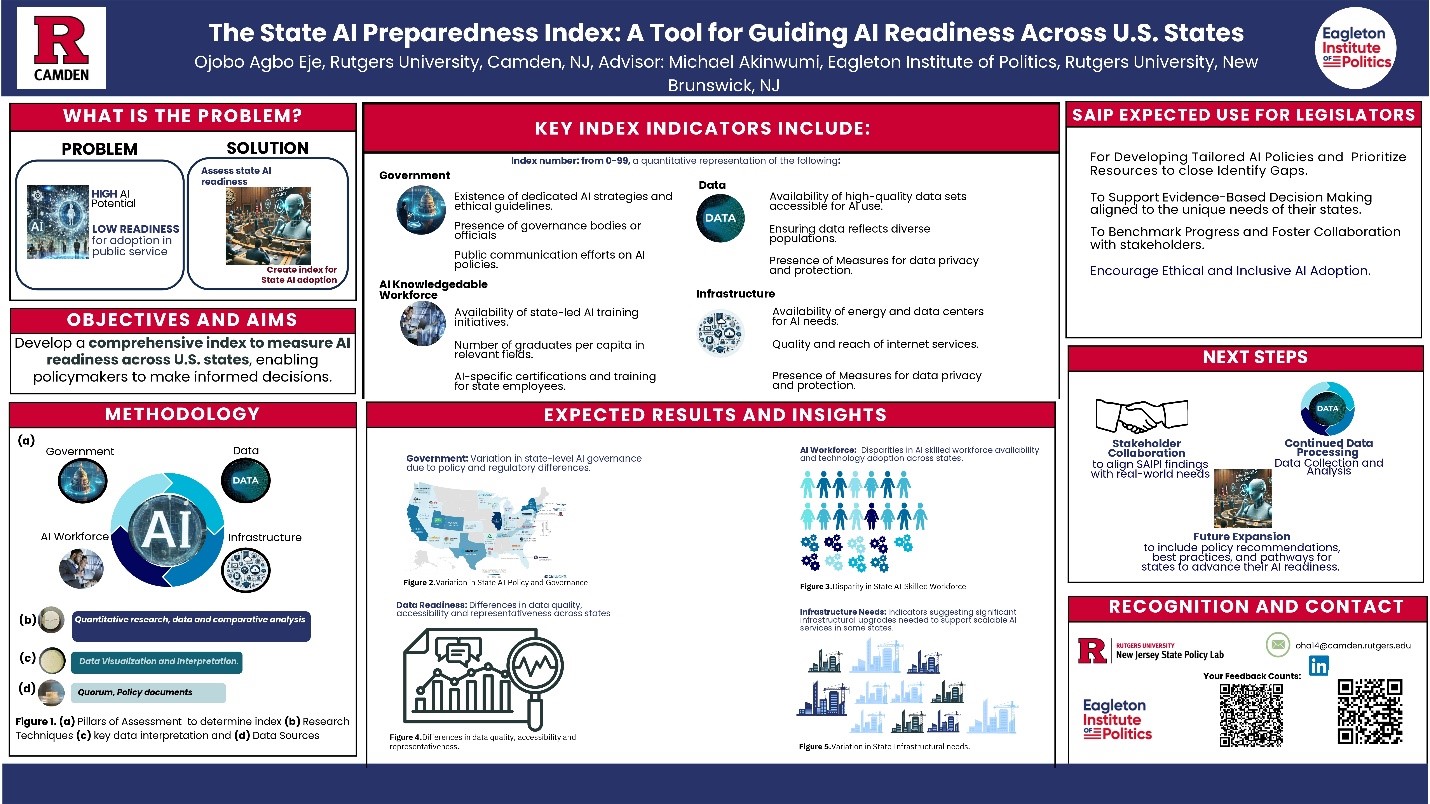

The State AI Readiness Index uses four pillars to measure states’ readiness to integrate AI into their public services: government, AI workforce, data, and infrastructure. These pillars will enable state policymakers, technology leaders, and other stakeholders to move toward integrating AI in ways that benefit residents of their states. The government pillar considers whether a state has policies to guide AI use responsibly, ensuring that AI applications align with public welfare. In addition, high-quality, unbiased data is essential for training AI systems that serve the public equitably.

The AI State Preparedness index will serve as a cornerstone for building safe, secure, and trustworthy AI governance frameworks—particularly at the state level—ensuring that technological advancements benefit society while mitigating potential risks. Further, it is closely connected to AI governance efforts in different states.[1]

Preliminary Findings

We have begun to see results from our initial analysis of the State AI Readiness Index, and they show significant variations across U.S. states in terms of preparation for AI integration and governance. Although we have experienced some challenges in developing the tool, we can now begin to understand these differences in AI readiness by evaluating the four key pillars based on the available data and gain a better of understanding of the state of AI readiness across the country. The following represent some of our initial conclusions:

- Clear Disparities in AI Readiness Between States

Based on our analysis of the available data, we categorized the 50 U.S. states into high, medium, and low readiness groups. We estimate that approximately 10 states fall within the high-readiness category, such as California, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, which have a comprehensive AI vision, well-funded AI research hubs, and strong private sectors driving innovation. California, for example, benefits from Silicon Valley’s AI ecosystem, while Massachusetts has world-leading AI research institutions like MIT and Harvard. Approximately 30 states fall within medium AI readiness, including Texas, Illinois, and North Carolina. They have made notable progress in certain areas, such as private-sector AI adoption and university-led research, but still lack fully developed, statewide AI governance strategies. Low-readiness states like West Virginia, New Mexico, and South Carolina have minimal AI-specific policies, limited AI workforce initiatives, and little formal coordination between state agencies and research institutions.

- State Governments Are at Significantly Different Stages of AI Integration

While some states have fully developed universal AI strategies, others rely on ad hoc legislation or individual agency initiatives. California, Massachusetts, and Illinois, for example, have detailed AI policy frameworks, clearly outlining goals for AI adoption in public services, ethical AI use, and AI-driven workforce development. Texas and North Carolina have passed AI-related legislation but lack a centralized AI strategy to guide broader AI integration efforts. West Virginia and South Carolina have little to no dedicated AI policy beyond general data privacy or cybersecurity regulations.

This uneven landscape underscores the importance of cohesive, statewide strategies. States with integrated frameworks are better positioned to align efforts across agencies, attract AI-related investment, and safeguard public trust through consistent, ethical deployment.

- Private Sector and Academia Drive AI Innovation in Many States

In areas where state governments have not fully embraced AI readiness, universities and private companies are filling the gaps. For example, in New York, institutions like NYU’s Center for Responsible AI and Cornell Tech are actively shaping AI policy discourse and ethical frameworks. In Massachusetts, MIT plays a central role in driving AI research and providing expertise to the state’s AI task forces and working groups. Meanwhile, California’s robust AI ecosystem is supported by partnerships between institutions like Stanford University and UC Berkeley, and corporate hubs in Silicon Valley such as Google, OpenAI, and Salesforce, which often influence national AI policy conversations.

In states like Texas and Illinois, strong private sector involvement in AI—particularly in cities like Austin, a growing tech hub, and Chicago, home to several AI startups and Fortune 500 companies—has spurred some innovation, but these efforts are not yet matched by comprehensive state-led AI strategies. In contrast, states like New Mexico and West Virginia, with smaller tech ecosystems and fewer major research universities or corporate tech players, tend to lack both public and private infrastructure for AI governance.

This pattern highlights a broader trend: states with larger and more mature tech ecosystems are more likely to build the cross-sector networks needed to support AI readiness and governance. Recognizing and fostering these ecosystems is key to AI development across the U.S.

- AI Workforce Gaps Pose Challenges

Access to broadband, cloud computing infrastructure, and AI education programs remains highly uneven across states. California, New Jersey, and Massachusetts have strong AI workforce pipelines, with universities offering AI degrees and training programs for government employees. Texas and Illinois have growing AI workforces, but state-funded AI training remains limited. West Virginia and New Mexico struggle with a lack of AI education programs, limited internet access in rural areas, and minimal investment in AI research facilities.

Presenting at the AAAS Conference

The project hit a significant milestone in February when one of the researchers, graduate student Ojobo Agbo Eje, presented the research at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) National Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts. The experience provided an opportunity to share the project idea, plan, and impact with researchers and stakeholders and was also a platform to receive important feedback.

This invitation to present at the AAAS represented a key moment for the project. The poster and presentation—made possible in large part by a grant from the New Jersey State Policy Lab—provided a broad overview of the State AI Readiness Index, outlining the methodology and emphasizing preliminary findings. During the presentation, discussion included the methodology used to assess AI readiness, variations in readiness across high, medium, and low-ranked states, and potential applications of the AI Readiness Index for state governments, policymakers, and researchers.

Attendees—including policymakers, researchers, and industry professionals—asked several thought-provoking questions during the presentation, including:

- What methods were used to normalize and weigh the different metrics for the four pillars?

- What role does private-sector AI investment play in a state’s overall readiness?

- Are there other research works or publications that can validate the possible effectiveness of this work?

- Beyond policymakers, which other groups could benefit from this novel idea?

These questions, along with the interest shown by meeting attendees, reinforced the need for state-level AI strategies and provided inspiration for refining our methodology.

Ongoing Project Challenges

As we continue with the projects next steps, three key challenges have emerged and continue to be relevant:

- Inaccessibility of State Data: One significant challenge has been inconsistent and incomplete data compilation processes across states. While some states publish clear strategic visions for AI adoption within their states, others have only ad hoc collections of executive orders or legislative bills. Still others have little to no official documentation whatsoever. Additionally, measuring AI workforce development is difficult due to a lack of state-specific employment and education data related to AI. This—and other, more detailed information—is not readily available on most state websites, making it difficult to assess how well a state prepares its workforce for AI-driven industries.

- Variability in AI Readiness: Not all states approach AI with the same level of urgency. High-readiness states like California and Massachusetts have comprehensive AI strategies, strong research ecosystems, and substantial private-sector investment. Meanwhile, low-readiness states struggle with limited funding, a lack of AI policies, and minimal AI-focused education initiatives. Due to the significant gap between readiness levels among states, understanding how lower-ranked states can catch up is more crucial to this project than we may have initially understood.

- Engaging with Stakeholders: Accessing state policymakers, AI task forces and government agencies has been challenging. While some states have proactively shared relevant data online with clearly stated avenues for contacting officials, others do not have a clear-cut process for connecting with officials who can assist with this project.

Next Steps for the State AI Readiness Index Project

Regardless of these challenges, we are looking ahead and focusing on several key areas to continue to enhance this project:

- Refining the AI Readiness Index Methodology: To facilitate the production and publication of a minimum viable outcome, we improved the methods to focus on AI readiness in a few states (including states with high, medium, and low readiness). This will create a template with which we can expand to other states when and where data is inaccessible. We are also reviewing our weighting and scoring methodology to ensure a more accurate reflection of AI readiness. These adjustments include adjusting indicators within each pillar.

- Expanding Research and Data Sources: To enhance our findings, we are seeking new data sources from AI-focused legislation and policy reports, AI adoption trends in state governments, and meetings with professionals and researchers working on similar projects nationwide. Expanding our stakeholder relationships will give us broader access to state-level data and provide more actionable insights.

As we continue refining the index and expanding our research, we welcome and seek collaboration with policymakers, researchers, and industry experts interested in shaping AI’s future at the state level. Understanding this quickly growing consequential field is as imperative as it is challenging, and we invite you to share your insights, data, or feedback on AI adoption in your state. For those interested in learning more or providing feedback, you are welcome to reach out to policylab@ejb.rutgers.edu, and we will gladly connect you with the researchers on this project.

References:

[1] https://policylab.rutgers.edu/the-state-ai-preparedness-project/