R/ECON’s next economic forecast is slated for release in mid-summer, followed by another forecast in the fall. As we track the latest state data and national outlook, we (much like everyone else) have been closely following the news on tariffs, the Fed’s potential actions, and associated fluctuations in the financial markets. While tariffs don’t enter directly into our state economic model, their effects are incorporated through their impact on the outlook for various national indicators drawn from Moody’s national forecast. These effects impact the economy (and the state forecast) in multiple ways, adding additional layers of complexity and uncertainty to the already tenuous task of predicting the direction of the national and state economy.

First, before tariffs are even enacted, their announcement and expectation can begin to affect consumer and business decision-making. This was already seen in the first quarter of this year, when national GDP declined by 0.2%.[1] This decline was primarily due to a surge in imports, with businesses looking to stock inventory ahead of the Trump administration’s “reciprocal” tariffs, and consumers rushing to purchase cars ahead of 25% tariffs announced on foreign auto imports.[2] These changes in behavior and their reflection in jolts to economic indicators, while likely temporary, can cause distortions in the outlook at both the national and state levels.

Once enacted, tariffs themselves can have complicated effects, including[3]:

- Increases in employment through onshoring of production in some industries, with job losses in other industries reliant on imported intermediate goods.

- Higher prices, but possible increases in employment and wages resulting from reduced foreign competition.

- Economy-wide inflation, with further implications for Fed policy and the broader economy.

Macroeconomic models strive to capture the impact of these anticipatory and reactive market behaviors, which can be difficult even when tariff levels are known and the historical relationship between price levels and other economic indicators is well understood. Policy uncertainty is always an additional factor affecting forecast accuracy, and is sometimes addressed through statistical approaches that account for the probability of certain conditions. Forecasts generally rely on a foundation of assumptions representing the best guesses as to the direction of fiscal and/or monetary policy. A baseline forecast generally represents the middle ground of multiple sets of assumptions reflecting variation in expectations for fiscal and/or monetary policy, with additional scenarios reflecting the outcomes of more optimistic or pessimistic sets of assumptions and expectations.

Thus, the current difficulty in forecasting the economy at the national or state level emerges less from any difficulty in analyzing relationships between variables or even addressing garden variety uncertainty, but in identifying what the assumptions of the baseline scenario should be. The ongoing series of tariff hikes, pauses, and rollbacks (a helpful timeline can be found here)–whether strategic, chaotic, or both–has made this task increasingly difficult. Most recently, the U.S. Court of International Trade blocked the Trump administration’s imposition of most of its reciprocal tariffs.[4] This decision is awaiting appeal by the administration, which will cast further uncertainty on the direction of policy. [As I write this, my wife has informed me that a federal appeals court has now stayed the Trade Court’s ruling, while almost simultaneously a second federal court has again rejected the president’s use of emergency powers to impose tariffs.[5] QED.]

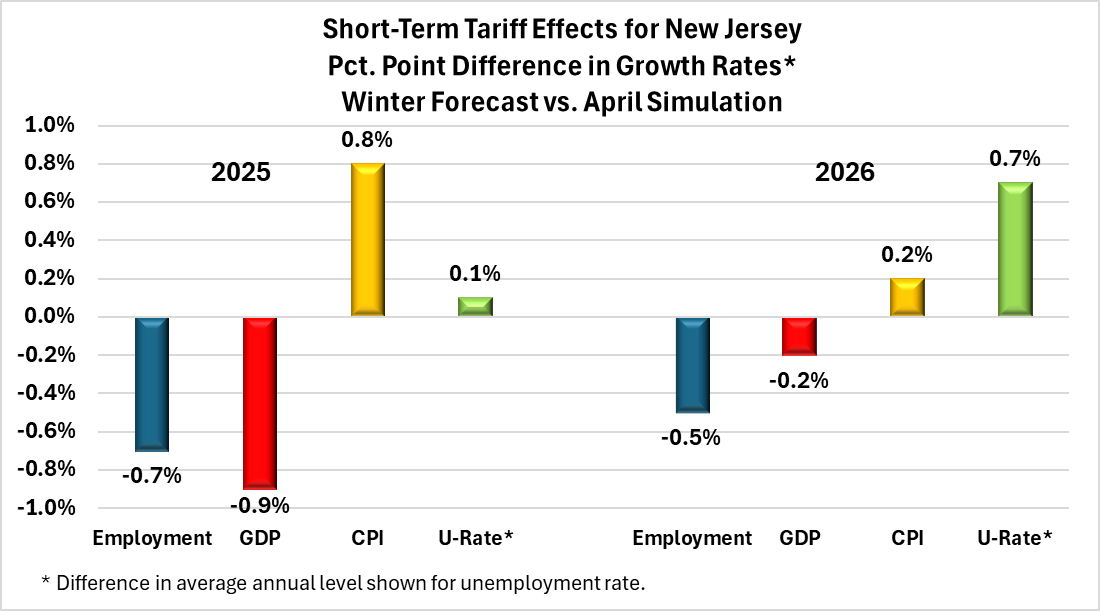

Earlier this month, we conducted a “quick and dirty” simulation of tariff impacts for New Jersey based on Moody’s baseline national forecast for April. [Note: This “quick and dirty” simulation was based on unrevised state data through the second quarter of 2024 and did not reflect revised employment data for last year or incorporate data for the most recent quarter(s). Our forthcoming summer forecast will be based on the most recent available data for the state.] Our experiment found significant implications (see chart below) for the state economy, even in the case of a national baseline forecast expectation that the Trump administration would back off of the highest tariffs and that most tariffs would be removed by 2026 (with a 20% rate on China lasting throughout the Trump presidency).

Moody’s May forecast saw some increase in the baseline tariff assumptions, with the 10% base rate becoming the standard for most of the world, along with a 40% rate for China. Peak effective tariff rates in Moody’s May forecasts range from 22.8% in in the baseline and optimistic scenarios (decreasing to under 10% in 2026) to as high as 35.5% in the most pessimistic scenarios, with no rollback before 2028. Our next state forecast will reflect updated New Jersey data and the latest underlying assumptions of the national baseline forecast. Depending on the outcome of the pending court cases, these assumptions (and our recent simulation) could by then be obsolete.

References:

[1] https://www.bea.gov/news/2025/gross-domestic-product-second-estimate-corporate-profits-preliminary-estimate-1st-quarter

[2] https://www.reuters.com/business/stockpiling-ahead-tariffs-likely-hurt-us-economy-first-quarter-2025-04-30/, https://www.scrippsnews.com/politics/economy/car-sales-surge-ahead-amid-worries-over-auto-tariffs

[3] See the excellent detailed breakdown of these and other effects provided by the Economic Forecast Project at UCSB: https://efp.ucsb.edu/blog/community-policy-research/effect-tariffs-us-economy

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/28/business/trump-tariffs-blocked-federal-court.html

[5] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2025/05/29/trump-tariff-trade-emergency-powers-court/