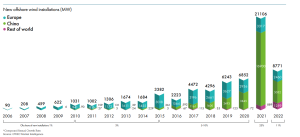

In 1991, the world’s first demonstration offshore wind farm began operating off the coast of Denmark[1]. Today, the UK leads the EU region with 15 gigawatts (GW) of capacity, followed by Germany with 8.5 GW, the Netherlands with 4.7 GW, and Denmark with nearly 2.7 GW[2]. Despite early adoption in Europe, China has rapidly developed offshore wind farms and become the global leader in installed capacity, as seen in the graphic below[3].

The offshore wind industry in the United States is in its early stages by comparison, with only one utility scale wind farm operating off the coast of Long Island[4]. In New Jersey, three developers have contracts to construct farms with around 5.2 GW of total capacity[5]. This presents an opportunity for the state to take proactive measures to distribute economic benefits and mitigate risks. Given the EU’s extensive history in this sector, analysis of the approaches these countries used to secure equitable outcomes can inform New Jersey policymakers.

The practice of developers providing community benefit funds is prevalent in both onshore and offshore renewable energy developments in the EU and UK and is becoming increasingly common in the U.S. One reason these funds are provided is an acknowledgement that communities affected by renewable energy projects should share in their benefits. Designating the community that receives benefits can be challenging for offshore wind projects, but typically funds are directed towards communities within the viewshed or those impacted by infrastructure such as cables or ports. The funds can support conservation efforts, scholarships, or other community needs as identified by stakeholders[6].

While community benefit funds are usually voluntary in offshore wind projects, Denmark’s distinctive approach includes mandatory community benefit funding administered through the government for communities impacted by renewable energy development. Though the impacts to community acceptance and support for renewables because of this are unclear, this approach does create a more democratic process of allocating benefits[7]. Given that New Jersey developers have committed over $230 million dollars in community benefit funds for a range of educational, energy burden, and other programs, the state should consider additional measures to enhance the process of allocating these benefits[8] [9] [10]. For example, metrics developed from the Energy Equity Project could be useful for developing standardized guidance and protocols, as well as future research priorities regarding the impacts of the funds[11].

Jessica Parineet is a Research Assistant with the New Jersey State Policy Lab and a graduate student in the Master of Public Policy program at the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy.

References:

[1] Orsted. (2019). Making green energy affordable: How the offshore wind energy industry matured – and what we can learn from it. In orsted.com. https://orsted.com/en/insights/white-papers/making-green-energy-affordable/foreword

[2] Costanzo, G., Brindley, G., Willems, G., Ramirez, L., Cole, P., & Klonari, V. (2024). Wind energy in Europe: 2023 Statistics and the outlook for 2024-2030. In windeurope.org. Wind Europe.

[3] Williams, R., & Zhao, F. (2023). Global Offshore Wind Report 2023. In Global Wind Energy Council.

[4] South Fork Wind powers up new era for American clean energy. (2024, March 14). us.orsted.com. https://us.orsted.com/news-archive/2024/03/south-fork-wind-powers-up-new-era-for-american-clean-energy

[5] State of New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. (2024, January 24). NJBPU approves over 3,700 MW of offshore wind capacity in combined award. www.nj.gov. https://www.nj.gov/bpu/newsroom/2023/approved/20240124.html

[6] Herrera Anchustegui, I. (2020). Distributive Justice, Community Benefits and Renewable Energy: The Case of Offshore Wind Projects. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3721147

[7] Jørgensen, M. L. (2020). Low-carbon but corrupt? Bribery, inappropriateness and unfairness concerns in Danish energy policy. Energy Research & Social Science, 70.

[8] New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. (2022, January 7) In the Matter of the Board of Public Utilities Offshore Wind Solicitation 2 for 1,200 to 2,400 MW- Atlantic Shore Offshore Wind Project 1, LLC. DOCKET NO. QO21050824

[9] New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. (2024, January 24) Order Approving Leading Light Wind 2,400 MW Project as a Qualified Offshore Wind Project. DOCKET NO. QO22080481

[10] New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. (2024, January 24) Order Approving Attentive Energy Two 1,342 MW Project as a Qualified Offshore Wind Project. DOCKET NO. QO22080481

[11] Energy Equity Project, 2022. “Energy Equity Framework: Combining data and qualitative approaches to ensure equity in the energy transition.” University of Michigan – School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS).