Many New Jersey parents felt the sting of reduced childcare access during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, the childcare landscape has not made a recovery that meets the needs of working families and their young children.

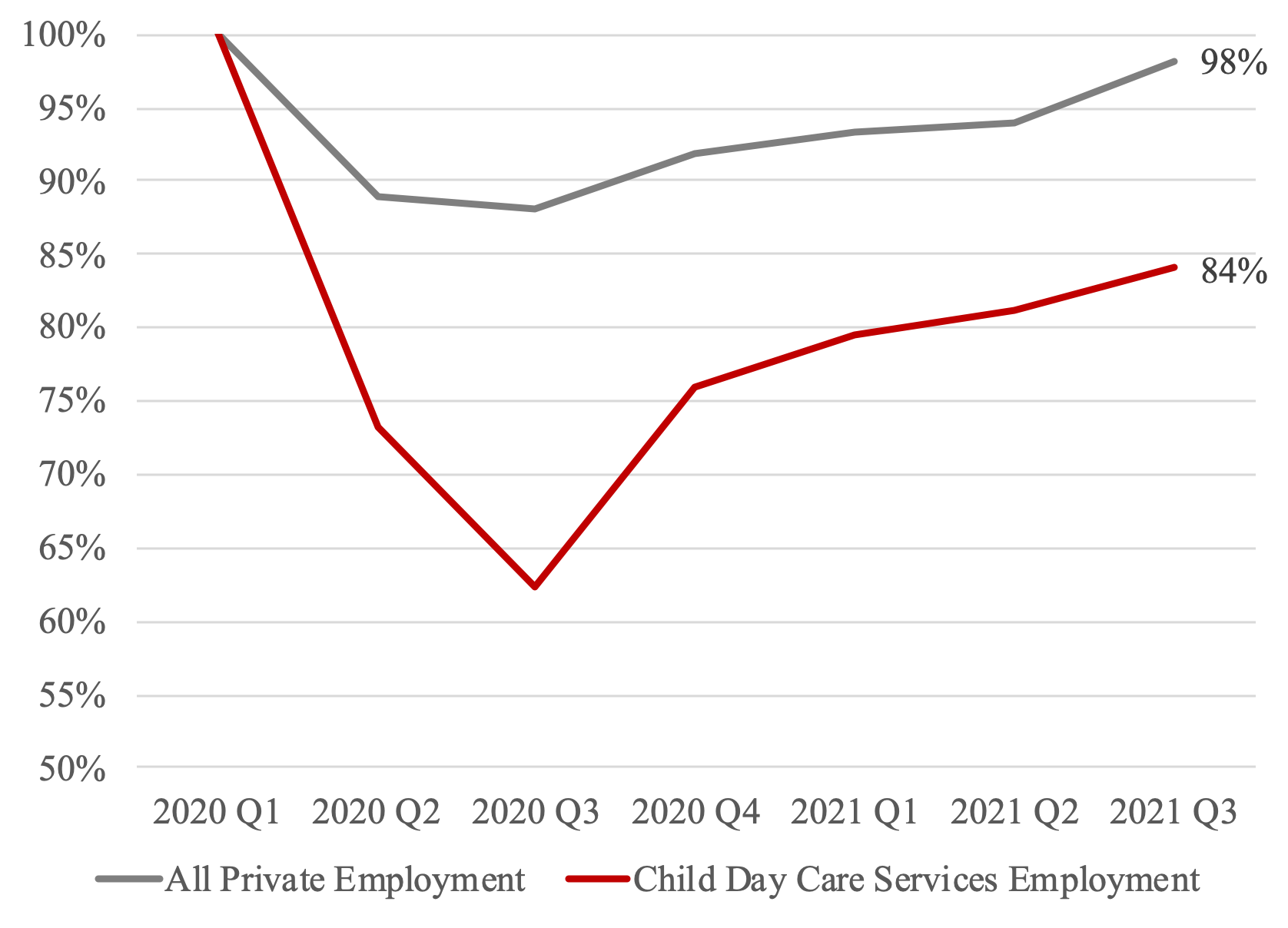

Our analysis indicates that the childcare workforce remains substantially below its pre-pandemic levels. In fact, compared to the first quarter of 2020, overall employment in New Jersey recovered by the third quarter of 2021. But the childcare workforce was still just 84% of its pre-pandemic workforce. As Figure 1 illustrates, in the third quarter of 2020, the state’s childcare workforce had shrunk to just 62% of its first quarter levels, from an estimated 37,825 childcare workers to 23,608 workers. Overall employment in New Jersey shrank less dramatically in 2020, hitting a low in the third quarter of 2020, when employment levels were 88% of those in the first quarter.

Figure 1. New Jersey employment as a share of 2020 Quarter 1 levels

Note: Sample limited to private sector employment in New Jersey. Child Day Care Services employment categorized according to NAICS 4-digit industry codes.

Source: Center for Women and Work analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Quarterly Workforce Indicators.

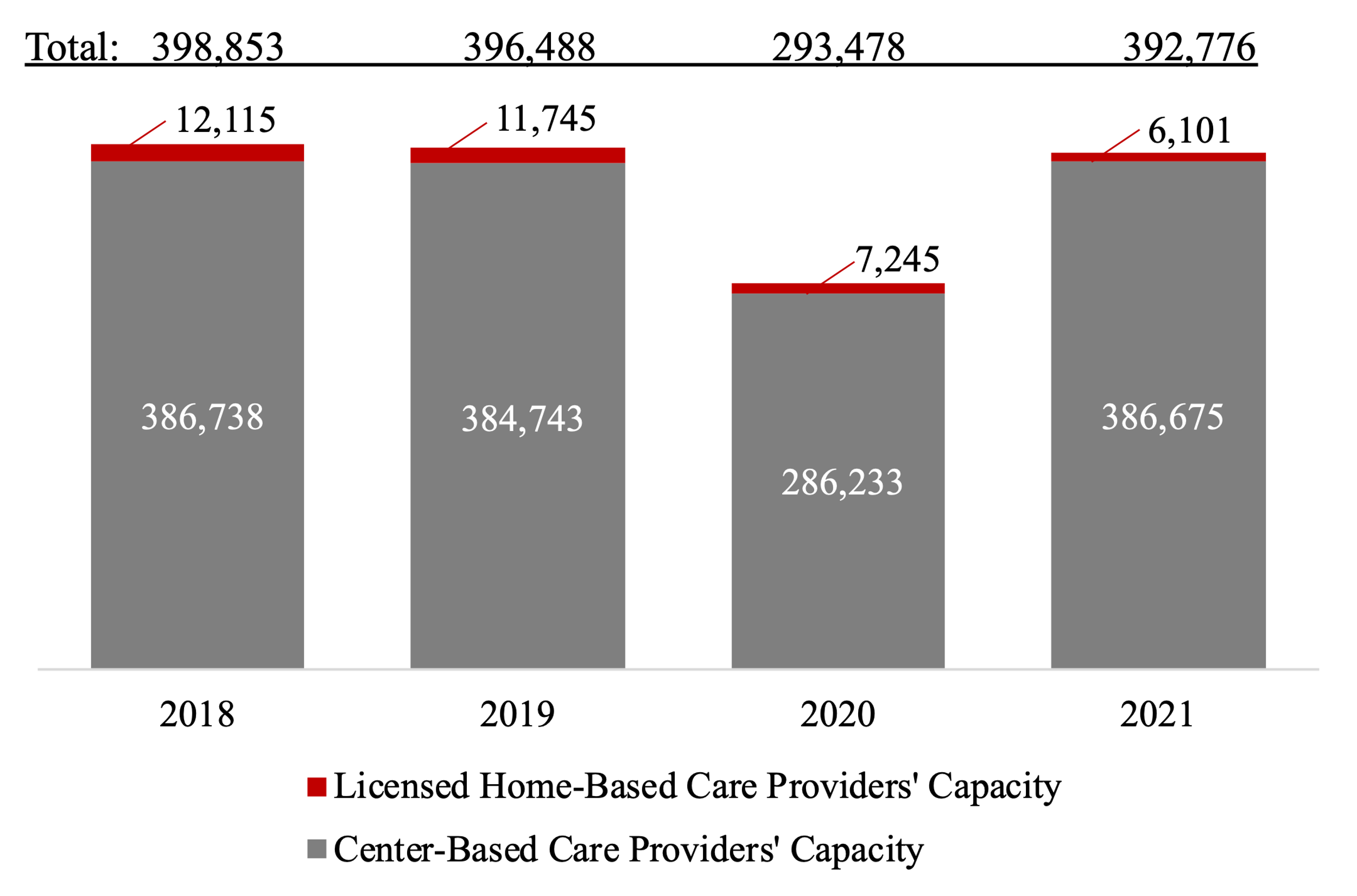

These employment figures suggest that childcare capacity in the state is limited compared to its pre-pandemic levels. Indeed, New Jersey’s total childcare capacity fell by 26% from 2019 to 2020, from an estimated 396,488 total licensed childcare slots to 293,478. As of 2021, childcare capacity still has not recovered to its 2019 level, with a gap of 3,712 spots relative to the pre-pandemic level.

Figure 2. Number of licensed childcare slots in New Jersey

Source: State of New Jersey Department of Human Services Division of Family Development

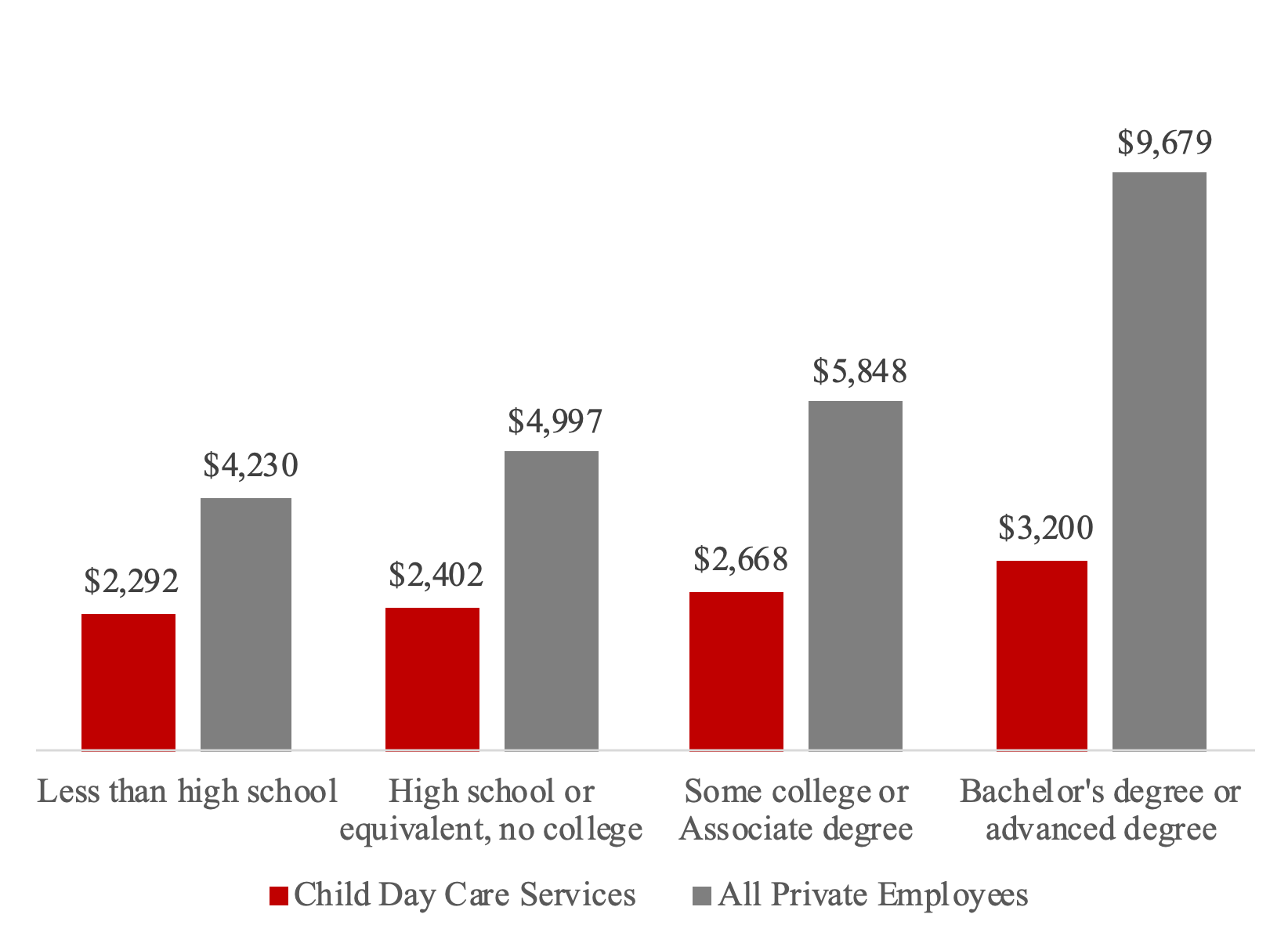

How can we support the childcare industry and its workers? One approach to recovering the childcare workforce is to focus on improvements in compensation. Some may suggest that improving educational access for childcare workers is sufficient, but such a policy needs to be accompanied by corresponding wage increases. The data indicate that returns to education in the child day care industry are poor. As shown in Figure 3, those with bachelor’s or advanced degrees only earn an average of $908 more in monthly wages than those with less than a high school diploma. Further, childcare workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher earn just one-third (33%) of their equally educated counterparts working in the private sector in New Jersey. This means that workers with higher education have very little incentive to stay in the childcare industry.

Figure 3. Average monthly earnings in 2020, by education

Note: Sample limited to private sector employment in New Jersey. Child Day Care Services employment categorized according to NAICS 4-digit industry codes.

Source: Center for Women and Work analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Quarterly Workforce Indicators.

This inequity is especially problematic given the well-documented positive returns to child welfare and care quality that come with caregivers’ improved educational attainment. Some states have recently implemented subsidy programs that provide licensed childcare workers with additional monthly income.

Another step which may serve to improve the supply of the state’s childcare workforce is to establish an employer childcare tax credit. Currently, several states provide tax credits designed to incentivize employers to either provide childcare directly, contract with current providers for childcare for their employees, or otherwise help expand the supply of childcare for their employees. This may be especially useful in New Jersey’s rural communities, where childcare deserts are common, as well as for those working in industries which require evening or overnight work when childcare provisions are especially sparse.

Ultimately, without continued efforts to improve the childcare landscape in New Jersey, many childcare providers will not be able to sustainably provide care, and many families will continue to face economic hardship. Prioritizing the care economy in the next several decades will be pivotal to New Jersey’s economic success.