Frontline essential workers were lauded as heroes in 2020 during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, but ultimately, little was done by way of supporting such workers. This meant that frontline workers face extraordinary risk, but with little reward. In New Jersey, the majority of frontline essential workers are women, and are often women of color.

We define “frontline workers” as the New York City Comptroller did in their profile of frontline workers in New York City. “Frontline workers” are workers in any of the following six industry groupings.

- Grocery, Convenience, and Drug Stores

- Public Transit

- Health care

- Trucking, Warehouse, and Postal Service

- Building Cleaning Services

- Child Care and Social Service

In 2020 over 63% of the New Jersey’s frontline essential workers were women. This percentage for New Jersey is virtually the same as New York City, where the heroics and hard work of frontline workers made national headlines during the height of the pandemic.[1] In non-essential industries, just 45% of the workforce were women.

Among working women, 11% in non-frontline industries were Black compared to 20% of women working in frontline essential industries.

Figure 1. Frontline essential workers in New Jersey, women by race, 2020

Note: Sample limited to New Jersey workers. Frontline workers are classified as those working in any of the following industries: health care; childcare and social services; building cleaning services; public transit; trucking, warehousing, and postal service; grocery, convenience, and drug stores.

Source: Rutgers University’s Center for Women & Work analysis of survey-weighted 2020 1-year ACS microdata

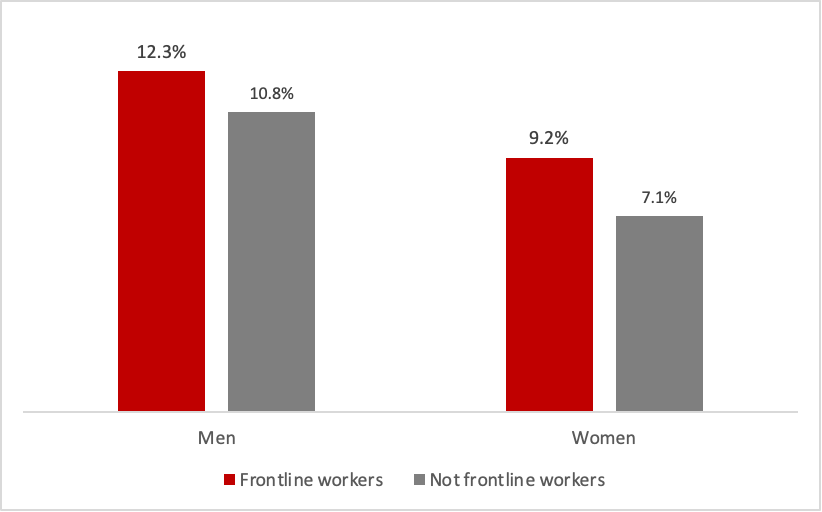

This suggests that women, and especially Black women, were often in public-facing jobs which had risk of COVID exposure. However, frontline workers in New Jersey often do not have health insurance coverage: 12% of men and 9% of women in frontline industries do not have health insurance coverage.

Figure 2. Workers without health insurance

Note: Sample limited to New Jersey workers. Frontline workers are classified as those working in any of the following industries: health care; childcare and social services; building and cleaning services; public transit; trucking, warehousing, and postal service; grocery, convenience, and drug stores.

Source: Rutgers University’s Center for Women & Work analysis of survey-weighted 2020 1-year ACS microdata

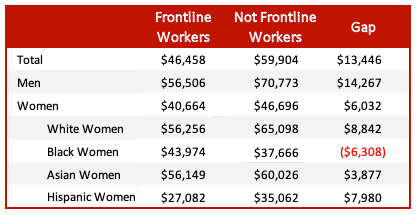

New Jersey workers in frontline industries also often make less money than those in other fields. In fact, women working in frontline industries earned just $40,664 on average in 2020. This is less than the average annual earnings of men working in frontline industries ($56,506) and less than the average annual earnings of women working outside of frontline industries ($46,696). Earnings for Hispanic women in frontline industries were especially low, at just $27,082 annually in 2020. Notably, Black women earn more on average in frontline industries than they do in non-frontline industries.

Figure 3. Labor income for frontline workers

Note: Sample limited to New Jersey workers. Frontline workers are classified as those working in any of the following industries: health care; childcare and social services; building and cleaning services; public transit; trucking, warehousing, and postal service; grocery, convenience, and drug stores.

Source: Rutgers University’s Center for Women & Work analysis of survey-weighted 2020 1-year ACS microdata

Lastly, women working in frontline industries were slightly more likely to have children (54% had children) than women working in occupations outside of the frontline essential industries (50%), meaning they also faced care burdens that made regular participation in their jobs more challenging.

Thus, even with a potential for higher workplace COVID exposure rates and issues with childcare difficulties, frontline women workers faced greater income precarity and had less health support than those working in non-essential industries. With the pandemic stretching on into 2022, it is important that New Jersey find ways to support its frontline essential workforce. This means targeted support for women, particularly women of color and women with children. Without health insurance coverage and reliably higher incomes, many essential workers will face difficulty choices in continued labor force participation, and others may face housing and food insecurity as rental protections subside and stimulus payments end.

References:

[1] https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/new-york-citys-frontline-workers/#who-are-our-frontline-workers